Reconciliation (noun)

1. the restoration of friendly relations 2. the action of making one’s belief compatible with another; harmonization

When you read fiction a lot, as I do, it becomes second nature to step into other worlds and then step back out of them again. I can walk into and out of mysteries and dramas and fantasy worlds with ease. I’m well-practiced; I can move fluidly from one to the next, identifying the markers of good storytelling and I tend to focus my attention on author choices. I love to examine the techniques they use to bring characters to life. It’s not unusual for me to think about them long after I set them down.

Reading Native American fiction has been no different for me. It has always had the same effect: I can walk into it, look around and admire it, then walk back out. I can be in awe of the way Louise Erdrich brings the Kashpaw and Lamartine families from Love Medicine into sharp focus. I can run my hands over the table that Joy Harjo sets in the poem Perhaps the World Ends Here and then I can close the book and walk back into my white life and the white culture I belong to, holding them at arm’s length.

That all changed for me last year. As a literature teacher, I tend to live primarily in the land of fiction. While there is nonfiction present in the curriculum at our high school, zero percent of the nonfiction happens to be Native American. Until I read Neither Wolf Nor Dog, my exposure to the real-life Native experience was essentially just the reservation that I drove through occasionally when we lived in South Dakota. You would think that South Dakota, so rich in Native history, would be an ideal place to learn and understand the Native experience. Sadly, I can’t say that was very true for me. (I fully recognize I’m probably going to be disowned by a whole lot of family members in a minute or two for saying this, but I have to say it like I saw it, even if they don’t like it.) What I observed during my youngest years, is that it’s totally fine for roads and rivers and counties and buildings to have Native names as long as none of the Natives actually interact with you personally. I really can’t remember anyone around me speaking often or kindly about Native peoples. Maybe they did and I was just too young to know it, but I had a distinct impression growing up that Native people were “other” and they were separate from me in every way.

NWND isn’t technically nonfiction – but it does center a white perspective as the foil to Dan the Elder’s protagonist, and the effect on a white reader is powerful. After that book, I began picking up other works of memoir and nonfiction, such as Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and Chief Joseph. In the past year and a half, I have learned and grown in a way I had not anticipated. Which brings me to today, December 26th.

I’ve read a great deal and watched a number of documentaries about the Dakota 38, the men who were executed in Mankato the day after Christmas by the order of President Lincoln. The story is not a simple one; it is filled with all the complexities you might expect of a tumultuous time in our State’s history. There are no winners – only regret and sorrow and loss. Today a beautiful memorial stands in the place of the executions, and every year the Dakota 38+2 Memorial Ride arrives on the site to say a prayer of Reconciliation and Healing. Reconciliation: an act of restoration, intended to restore harmony between two peoples, White and Native.

I wanted to go to the ceremony today in the worst way; I wanted to be there myself, to see and hear and listen and continue to learn. Circumstances forced me to watch it online – I was driving through Mankato to pick Emma up at the airport, but much much later than the riders would be there. So I watched it at home. Fears No Enemy spoke beautifully, and I was very moved by both the ceremony itself and the 17-day, 350-mile horseback ride the riders made in honor of their ancestors.

Later in the afternoon, I began my trek to the cities. As I neared Mankato, I was suddenly seized by inspiration – I just had to stop and visit the park. Even though it would be empty, the memorial is permanent, and it just felt right that I stop and say a few words of my own. I pulled off onto Riverfront Drive and waited at the stoplight by the Cub Foods. Something caught my eye – there is a Smoke Shop off to the left, and I found myself turning into the parking lot. I have learned a lot about the offering of tobacco – when it is Wakan and how it should be given. I parked and gave myself a little pep talk in the car because 1. I have never been to a smoke shop. 2. I have no idea what kind of tobacco is the “right” kind of tobacco. 3. I still operate under the “I’m a teacher and what if somebody sees me and thinks I’m setting a bad example” way of thinking most days, especially living in small-town conservative USA. And 4. I have no idea if this is something a White person should do or not. And 5. Did I already say I have never been in a smoke shop? Ugh. I reminded myself that I’m a fully grown person and I got out of the car.

God Bless the smoke shop worker. I stood, paralyzed, inside the door, completely out of my element and on the verge of bolting. This kind young man took pity on my pitiful self and said, “Can I help you?”

I blurted out, “I need loose tobacco.”

“Okay, here’s the case with tobacco. Do you know how much or what kind you need?”

What? You’re asking me questions? I hate being uncertain of myself – it’s not a comfortable feeling and I avoid it at all costs. I scanned the case – there was a section clearly labeled “Ceremonial Tobacco.” It had brightly colored packets emblazoned with Natives wearing headdresses and holding peace pipes. As I stood there, awkwardly fumbling for words, I had thoughts racing through my mind in rapid succession. What if ceremonial tobacco is different than the kind my dad smokes? Am I supposed to buy something special? Should I buy this packet with a Native American on it? What if it’s a White-owned company capitalizing on stereotypical Native imagery? That’s not good, I don’t want to encourage that. But what if it’s a Native-owned company? Then I DO want to encourage that. What if a White person isn’t supposed to have ceremonial tobacco? I don’t want my goodwill to be done poorly. Then – Holy crap, tobacco is EXPENSIVE! Ack! I had no idea! I better just get the kind my Dad smokes so it doesn’t go to waste. I hope the Great Spirit will understand; waste of resources might be worse than a well-intentioned White girl picking up the wrong type of tobacco.

I swear all of that happened in my head in the space of two seconds. I finally said, “Do you have something cherry flavored? I think my Dad likes that.”

The nice kid packaged up my $15 tiny pouch of tobacco and then he CARDED ME. Bonus points to him for that – this old lady sure appreciated having to dig out my driver’s license for the first time since I renewed it almost two years ago.

I fled to my car where I sat for a few minutes trying to recover my sense of security. Next thing’s next – I know that offering tobacco so that it is Wakan – sacred – comes under certain conditions. I had to do at least one thing right since I probably totally messed up the tobacco purchase. I turned on my Google microphone and said this exact sentence into my search engine: “If a White person wants to offer tobacco at a sacred site, how are you supposed to do it?”

And guess what? Google has an answer. It came from the Indigenous Offices at Carleton College. I needed a fabric square, a piece of yarn or string, and tobacco. I ransacked the car until I came up with a small square of fabric that I usually use for my makeup. I spread it out on my lap and filled it with a corner of the tobacco from the pouch. The yarn or string I know should be personal – so I pulled the ponytail holder from my hair and wrapped it around the pouch and drove the next few blocks to Reconciliation Park.

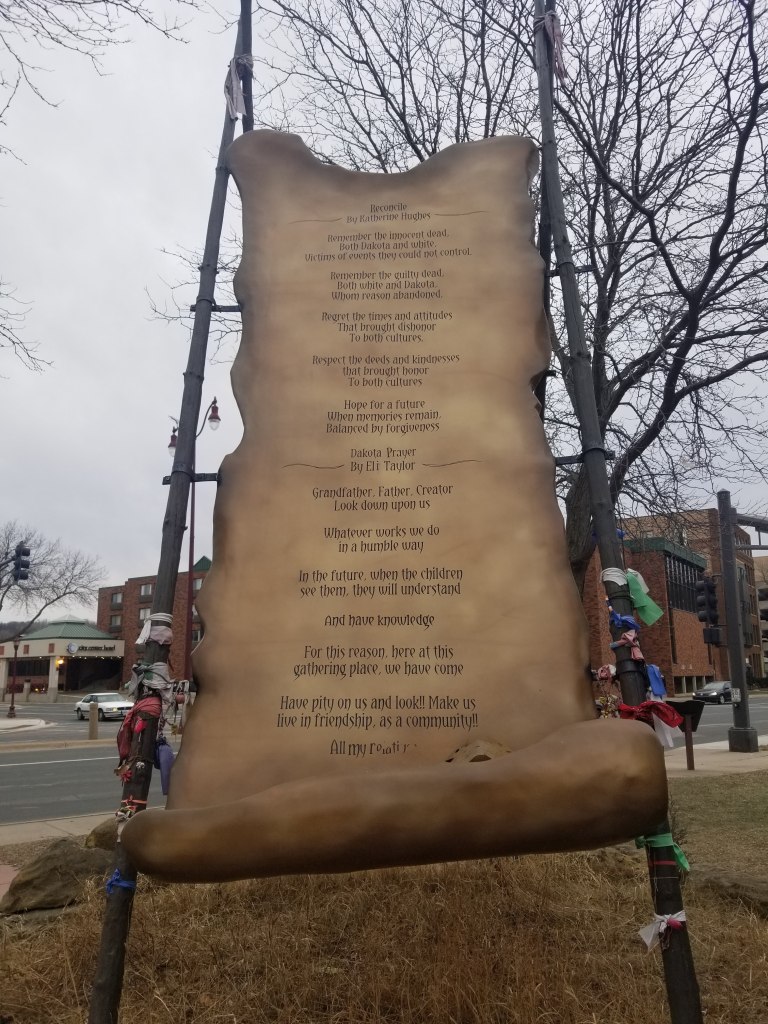

The last part of the offering turned out to be the easiest. You have to think good thoughts as you are making it, and you have to say good words. I thought about everything I’ve learned over the past two years. I thought about how I felt I was making real progress in my life toward openness and understanding. I rambled for a good five minutes about how I hoped that my own Creator and the Great Spirit were as close to each other as I suspect they probably are. I started to understand why sometimes Dakota prayers are super long. Once I got comfortable talking, the wind disappeared, I wasn’t cold outside at all, and thoughts just kept coming and flowing out of me. I hoped I was making reasonable sense. When I finished, I set the tobacco tie on one of the rocks beneath the memorial, and then I read the prayers out loud that are printed there.

“Remember the innocent dead, both Dakota and White, victims of events they could not control. Remember the guilty dead, Both White and Dakota, whom reason abandoned. Regret the times and attitudes that brought dishonor to both cultures. Respect the deeds and kindnesses that brought honor to both cultures. Hope for a future when memories remain, balanced by forgiveness.” ~Reconciliation, Katherine Hughes

“Grandfather, Father, Creator, look down upon us. Whatever works we do in a humble way, In the future when the children see them, they will understand and have knowledge. For this reason, here at this gathering place, we have come. Have pity on us and look! Make us live in friendship as a community.” ~Dakota Prayer, Eli Taylor

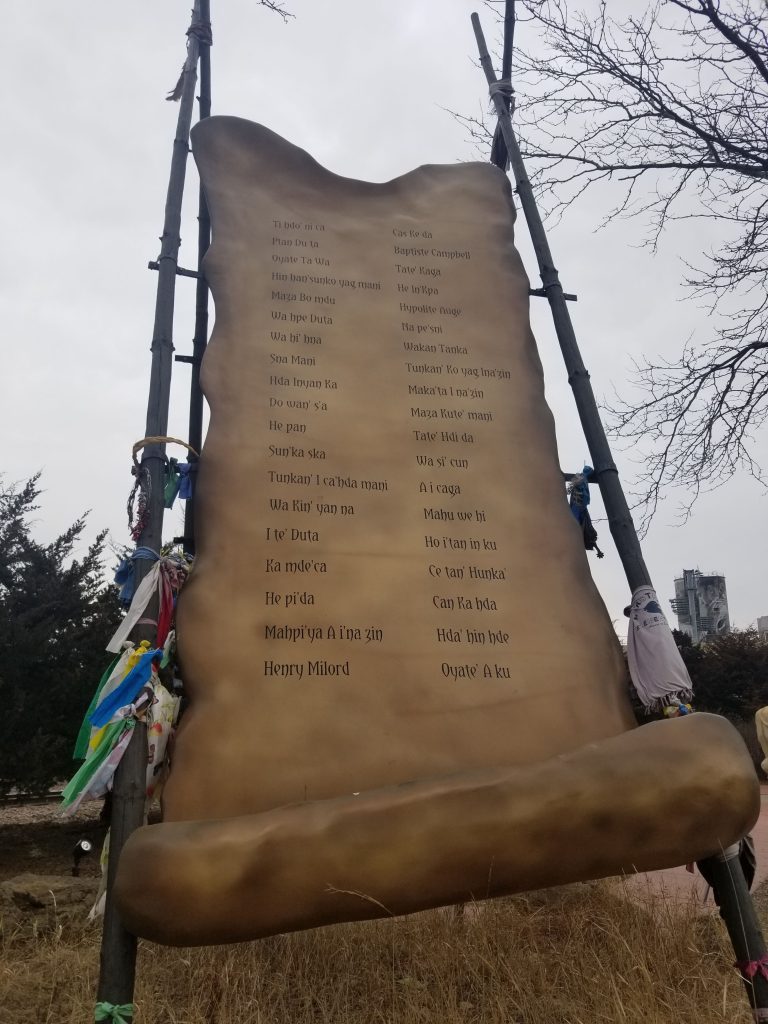

It was so quiet, so still, and so peaceful. I walked around to the other side of the memorial, where the names of the 38+2 are printed. I was whispering their names out loud to myself, trying to pronounce them, when I became aware of a line of cars at the stoplight right next to the park. I looked over and made eye contact with a college-age young man who leaned out of his car passenger window and yelled straight to me, “GO BACK WHERE YOU CAME FROM.”

And here’s where I pause. I pause because there really aren’t words. I’m tempted to stop here, because what can you say?

After a full day of thinking about it, I don’t think I will put on paper all of the thoughts that I had. I will just tell you what I did next. I WANTED to invite that young person to stop and have a conversation with me. He assumed, I’m sure, that I’m Native myself – I mean, why else would I be there, right? Why would a white girl be there? Instead, I ignored him, and finished the list. I said every name. Then I walked down to the river. I have always felt the most myself near the water, and I do all my best thinking and feeling when I’m near it. The river was flowing next to the park, and walked down and sat on a rock. The peace I had felt was gone – the wind picked back up and felt biting and cold again. I fumbled an apology to the wind – sorry for the ignorance and the hatred that seems to permeate everything these days. I hoped it didn’t cancel out my goodwill.

As I drove the rest of the way to Minneapolis, that great city named for the Sioux word meaning water, I thought about how every inch of the road travels over Native lands. Every other city, street, or county is named for or by the people who were here first. Go back where I came from? If I were Native, I would already be home. I’m new here, regardless of how many generations of my people were here before me.

Sometimes I think we have come so far. We, as humans, have overcome so much – but there is still SO much work to do.